One thing that has puzzled me since I was a child and watched Phyllis Schlafly seemingly single-handedly defeat the Equal Rights Amendment: why do they do it? Anti-feminists, I mean?

I can sort of see why people didn’t want to change in the first place, because people resist change. And I can see why people might take certain patriarchal narratives and behaviors for granted just because it’s never occurred to them to question them. But why would anybody be a deliberate anti-feminist activist? Especially a woman? Why would you decide restoring the patriarchy was the best, most important cause you could possibly fight for?

I particularly don’t understand why the church embraced it to the extent they did. During the 1980s, the evangelical church pretty much threw over anything it used to mean to have that faith, and started to replace it with patriarchal “culture war” doctrine. The preachers of the doctrine claim they were inspired by ABSOLUTE BIBLICAL NECESSITY TO OPPOSE FEMINISM GAYNESS AND ABORTION AND ALSO VOTING FOR DEMOCRATS, but even a cursory examination of the original text (that is, the Bible) reveals that claim to be nonsense.

So, why?

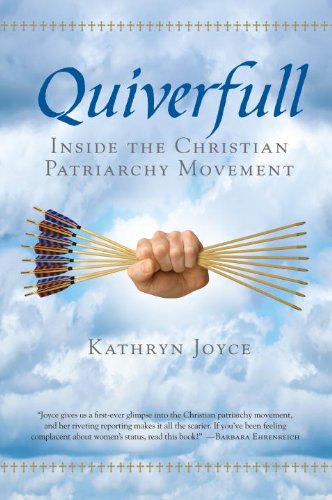

It was one thing I was hoping to get out of reading the Quiverfull book that remained as mysterious as ever when I was done. It seemed clear that it was in some way a reaction to the 1960s, to casual sex and freewheeling gender expression, but the actual cause and effect was a bit murky.

If you just want to control women for some reason, you can see why the particulars of Quiverfull might occur to you as a reaction to the 60s. My parents seem pretty typical of their generation: they got married in the 60s, my mom briefly worked to help my dad finish school, then she started having kids and stayed home to raise them. But a 6-year-old doesn’t need the same kind of constant attention as a two-year-old, especially not once they’re in school for a good chunk of the day. Eventually, she got bored. She was an excellent typist. So she went to work.

That narrative played out with families all across the country. Based on the theory that women tend to discover feminism (that is, working outside the home and earning their own money) when they’re not exhausted on a daily basis by the task of raising children, if you want to prevent feminism, you ensure that the babies never stop coming, and that she never gets the reprieve of sending them off to school. She never stops, catches her breath, looks around the empty, immaculate house and thinks “now what?”

And yet, still, why? Why is controlling women so important to some people? What are they getting out of it? What is this horrific shambling zombie patriarchy really for?

There’s some perception — among anti-feminists — that the old patriarchy provided men with “good family-wage jobs,” and that if only women weren’t out earning their own keep, these jobs would still be there, presumably awarded to every able-bodied white man right on the dot of his eighteenth birthday. But that’s getting cause and effect backwards. Women started entering the workforce in earnest during the 80s when the “good family-wage job” was already disappearing. It was rapidly diminished further by deregulation, union-busting, and other changes — all driven by the economic policies of Ronald Reagan, incidentally, a president who has been well-nigh sainted by the anti-feminist right.

History of the religious right part 1

She reveals that the ultimate motivation for the anti-abortion movement, and the religious right in general, was racism. In the 1970s, the federal government started denying tax-exempt status to racially discriminatory schools, which irked evangelical colleges (such as Bob Jones University) that wanted to continue to be racially discriminatory. This got conservative racist evangelicals into a feisty mood and ready to be rallied into a conservative Republican voting bloc. But they needed something to rally around that sounded a little bit nicer than “we hate the federal government for trying to make us not be quite so racist anymore.”

So they picked abortion, because they thought “WE HATE THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT FOR KILLING BABIES” had a nice ring to it.

Now everything falls into place. Yes, they were looking for a repeal of the 1960s. Specifically, they were looking for a repeal of the Civil Rights Movement. Natalism really was ultimately driven by nativism. Homeschooling was to take your kids out of wicked (that is, desegregated) public schools. Christian-specific manufactured pop culture was designed to be safe, insipid, and — yeah, now that I think about it — very, very white.

So, the question of “why patriarchy” makes more sense now that I can flip it on its head:

Patriarchy didn’t drive anti-abortion activism.

Anti-abortion activism necessitated patriarchy.

Anti-abortion activism was a cover for racism.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that all individuals involved are personally, consciously racist. Even though the evangelical churches of my youth were 99% white, I can honestly say I never once heard an explicitly racist message from a pulpit, Sunday School class, or fellow congregant.

But — and I really hope we’re starting to get this by now, so that we don’t have to argue this one point every single time it comes up — you can be part of a racist system without choosing to be. You can believe and perpetuate racist narratives without consciously being a racist yourself.

People with racist motivations are counting on that. They use dog whistles and coded language and bait-and-switch tactics specifically to get you to avoid noticing that you’re supporting a racist agenda. That’s why they have to pick something like abortion as cover. They know too much open racism turns many (most?) people off, and also, undermines the authority of their other claims. That’s why abortion has been so useful for them — they can shout “murderer!” to shut down every conversation before we get to the point of noticing their racism.

And — I’m just realizing this now, as I revisit my evangelical past — you can reject racist narratives because they are lies, without realizing they’re specifically racist lies. As a teenager I knew that lifestyle Christianity, with its paranoid in group/out group notions of what constitutes righteousness, was wrong. I didn’t notice it was racist. I noticed that its shallow, bland, suburban, clean-cut, white bread notion of what it meant to be a good person was false and superficial. I didn’t realize how important the “white” part of that was.

I noticed that people who wanted me to listen to music that glorified God kept trying to to get teenage me interested in Amy Grant, and never once thought to play me any Gospel. I didn’t get it at the time. Now maybe I do.

Back in May I spent a rainy Sunday morning in the Gospel tent at New Orleans Jazzfest. We joked about it being a spiritual experience, but, you know — it was. Gospel frequently reminds me of why I was ever a believer in the first place.

Gospel is joy. Gospel is personal redemption. Gospel is hope. Gospel is celebration. Gospel is Jesus as friend to the friendless, comforter to the suffering, the ultimate victory for those beaten down in this life.

Christianity is not about raising up the powerful and keeping down the humbled. It’s about raising up the low and bringing down the high, not to switch their places, but to make them equals.

Jesus preached equality. There’s just no way around that. He told us that all humans are equally flawed and equally glorious. Emperors and peasants, men and women, Jews and Samaritans, preachers and tax collectors — we are equal in the eyes of God. Our righteousness is determined by our actions, not by the accidental circumstances of our birth. Righteousness is about what we do. And I don’t mean “do” in a ritualized, following-the-rules sense. I mean, what we do in the world. How we treat each other. How well we express love to one another.

If you’re not loving your neighbor, you’re not following Jesus.

Doctrines of male supremacy, white supremacy and religious intolerance are not loving your neighbor. They’re bad. False. They might be, technically, “Christian” in a nominal, cultural-background sense. But they are not following the teachings of Christ.

In Samantha Bee’s narrative, when racism had to cloak itself in the patriarchy cult, the cult was thriving. But now that Donald Trump is just straight-up campaigning on a white supremacy platform, the power of the cult is fading. They don’t have to hide anymore. They don’t have to pretend it’s about “morality.”

It’s important to remember that it never was.

Hi Julie, I have appreciated reading this series. As a survivor of the quiverfull, patriarchal homeschool movement I found myself nodding along while reading. You obviously get it. I have a question for you. When you say “Doctrines of male supremacy, white supremacy and religious intolerance are not loving your neighbor. They’re bad. False. They might be, technically, “Christian” in a nominal, cultural-background sense. But they are not following the teachings of Christ” do you feel like the leaders of the movement aren’t “real” Christians? I’m curious to know your take on it.

That’s a good but complicated question, and I’m not sure I have a definitive answer. Conservative evangelicals are really keen to claim other groups, including politically liberal evangelicals, aren’t “real” Christians and I don’t want to follow in their footsteps. But I do want to make a distinction between all the disparate and sometimes contradictory things people mean by “Christian,” and also not let people get away with claiming too much territory by the way they use the word.

I guess that’s why I try to be as specific as possible, by saying things like “not following the teachings of Christ” rather than “not really Christian.” In a way, the church has always struggled with two somewhat contradictory takes on what it means to be a Christian: is it more important to affirm the mystical belief system involving Jesus (as in the Nicene Creed) or is it more important to do what Jesus said to do? If you are doing both, no problem, but if you are only doing one, it’s harder to say. I personally feel the teachings are more important, but it’s not really my call.

On the other hand, it’s not their call either.